Charles Clark served as a judge on the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit from 1969 until 1992. For his last eleven years on the court, he was the chief judge. Clark was the most significant Mississippi federal judge since L.Q.C. Lamar, who died in 1893 while serving on the United States Supreme Court. Though Clark never served on the Supreme Court, he came close twice. He also was the chairman of the Executive Committee of the Judicial Conference, which is the highest administrative position in the federal judiciary.

Clark was a fourth-generation Mississippian. His three immediate Clark ancestors were all lawyers. The first in the line was his great-grandfather, also named Charles Clark. That Clark was born in Ohio in 1810, moved to Mississippi in 1831, and was governor of the state at the end of the Civil War. The future Fifth Circuit judge was born on September 12, 1925, and grew up in Cleveland, Mississippi. Two years after he was born, his father died at age forty-two. The Depression hit two years later. Later the judge remarked simply, “times were pretty hard.” His mother took in boarders at their home. She died a few weeks after Clark started college.

In July 1943, Clark began active military duty in the Navy V-12 training program, in which college students engaged in regular studies and in military training. He first attended Millsaps College, then transferred to Tulane University. He was commissioned as a Navy officer in July 1945 and was serving on a ship in the Pacific when the war ended. After being released from the Navy in 1946, he attended Ole Miss law school and graduated in 1948.

Clark married Emily Russell of Jackson in 1947. Their six children are Charles, Emily, John, James, Catherine, and Peter. The Clarks made their home in Jackson.

Clark began his practice with the Jackson law firm of Wells, Wells, Newman, and Thomas. He returned to active duty in the Navy for almost two years during the Korean War. In July 1961, Clark formed a law firm with Vardaman S. Dunn and William Harold Cox, Jr. Clark gained a well-deserved reputation as a skilled litigator.

In addition to his private practice, from 1961 until 1966 Clark was a Mississippi Special Assistant Attorney General. Clark’s first case was to defend the state college board in the legal conflict on admitting James Meredith as the first African-American at Ole Miss. Attorney General Joe Patterson contacted Clark in 1961, said that the State would probably lose, but it like all defendants deserved a good defense. Clark’s representation of the state college board placed him alongside attorneys defending Governor Ross Barnett in his efforts to block admission.

The Fifth Circuit had numerous hearings and issued several opinions ordering admission. After Meredith’s admission on September 30, 1962, a riot began on campus that required the military to stop. Attorney Clark went to the governor’s mansion the night of the fighting, urging that Governor Barnett issue a statement to calm the situation. None was given.

Twelve days later, the en banc Fifth Circuit heard oral arguments in New Orleans on whether to hold Governor Barnett in contempt for ignoring the court’s orders. Attorney General Patterson had already assured the court the governor would comply with future court orders. A judge asked if Clark also was confident about the governor’s compliance. As two law professors later wrote, “Charles Clark faced one of those rare moments in the life of an attorney where his candor and courage were severely tested.” He answered, “I cannot make that assurance.” It was a dramatic and career-defining moment, when character was key. One judge commented to another when leaving the bench: “That is a young man that can be trusted.”

Summarizing Clark’s work in the Meredith case, Fifth Circuit Judge John Minor Wisdom more than a decade later said that “Charles Clark emerged as a shining star. . . . He argued vigorously, made the best of a bad case, was deferential to the Court, acted with dignity and grace, and conducted himself in every way according to the highest tradition of Anglo-American advocacy. He won my respect then and the respect of all the judges on our Court.” Author Jack Bass, who wrote about the Fifth Circuit in a book entitled Unlikely Heroes, concluded that Clark’s professionalism critically assisted the court in its resolution of Mississippi cases.

Fifth Circuit Judge Claude Clayton of Tupelo died in July 1969. The extremely favorable impression Clark had made on Fifth Circuit judges caused several to contact Senate Judiciary Committee Chairman James Eastland to urge Clark be named to the vacancy. Also helpful were calls made by President Nixon’s Attorney General, John Mitchell, to some of the judges. Judge Elbert Tuttle, a leader of the court’s liberal block, told Mitchell that Clark would be excellent:

I well remember my telling [Mitchell] that the President could do no better, that I knew [Clark] only as counsel appearing before the Court, but that experience had convinced me that [he was] not only possessed of the legal skills and ability required for such a position but that [his] frankness and openness with the Court had made a distinct impression on all of our members.

President Nixon nominated Clark to the Fifth Circuit on October 7, 1969. He was confirmed unanimously eight days later.

Clark was twice considered for nomination to the Supreme Court. In the fall of 1971, there were two vacancies on the Court. President Nixon quite publicly sent six names, including Clark's, to the American Bar Association for evaluation. Briefly, Clark seemed to be the President's choice for one of the vacancies. Ultimately, Lewis Powell and William Rehnquist were chosen, neither of whom was on the list of six. Clark again was considered in 1975. President Ford ranked Clark among the final four possibilities but chose John Paul Stevens.

The six-state Fifth Circuit had the most judges of any of the circuits, reaching twenty-six in 1978. Congress approved splitting the circuit, effective October 1, 1981. The Fifth Circuit lost its eastern three states, and retained Mississippi, Louisiana, and Texas. As the longest-serving active judge in the three western states, Clark was now the Chief Judge of the Fifth Circuit. Clark is fondly remembered as a splendid administrator, innovative and fair, who shared authority and kept his colleagues informed. His fellow judges were not only his colleagues but his friends. Fifth Circuit Judge Tom Reavley of Texas, a gentleman of the first order himself, said that it was Clark’s “special gift to lead naturally and easily. He kept a firm, but kind, hand on the tiller” of the court, always exhibiting good judgment and fairness.

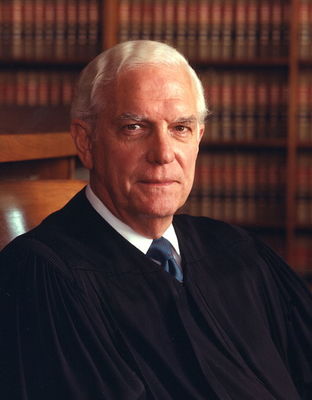

As chief judge, Clark had an additional benefit according to Circuit Judge Paul Roney of Florida. He said Clark looked “like Lord God Almighty, which helps if you're a judge. All he needed was a thunder bolt!” Asked about this comment, Judge Clark responded, “Well, if you can't play the part, you ought to look the part.” In fact, though, the tall, handsome, white-haired Clark was both the image and the reality of what a judge should be.

The pinnacle of Judge Clark's judicial service may have been his work on the Judicial Conference of the United States. On this committee are the chief judges of each circuit and an equal number of chief district judges. It is the policy-making body for the federal courts. Clark was chairman of the budget committee from 1981 to 1987. On January 1, 1989, the Chief Justice appointed Clark to be chairman of the Executive Committee of the Judicial Conference.

Just beyond his sixty-sixth birthday, Judge Clark resigned from the court in January 1992 in order to return to private law practice in Jackson. He rejoined his two former law partners, Vardaman Dunn and Bill Cox, who by then were members of the Watkins & Eager firm in Jackson. He was primarily involved in appellate advocacy, appeared a few times before his former court, and was a mediator. He completely retired in 2009.

During his twenty-two year career on the Fifth Circuit, Judge Clark authored over 2800 opinions. His work habits were remarkable. In addition to long hours during the week, Clark worked with his law clerks at the courthouse every Saturday morning. Fifth Circuit Judge Rhesa Barksdale said Clark was “always completely, and insightfully, prepared” on cases being argued before him. United States Supreme Court Justice Byron White called him “a great judge, a great leader,” and “a remarkably wise and intelligent man.”

A former law clerk, Rodney Smolla, later the dean of two law schools and the president of a university, wrote when Clark retired that his “grace and gentility are known to all in his professional and personal life. Every clerk who worked for him witnessed how he treated his colleagues, litigants, clerks and staff: with dignity.” Another former law clerk, John Henegan, said he was “patient, listened, was open to points of view different from his own, commanded respect as a person without creating any distinctions much less hierarchy between himself as judge and others as staff, clerk, or lawyer, and had a fundamental belief and confidence in the capacity of the law to guide and inform conduct.” A third former clerk, David Mockbee, called Judge Clark “a legal scholar, a gracious and caring mentor, a friend from my clerkship until his passing, and a gentlemen to everyone with whom he came in contact.”

Any description of Judge Clark cannot be complete without including his wife Emily, whom he playfully called his “bride of several summers.” She was his bride for 63 summers. Fifth Circuit Judge Grady Jolly said that Emily became as well-known in the Fifth Circuit as the judge himself, “appreciated for her natural kindness, soft grace, and unassuming dignity.”

Hanging on the wall in his court office, then later at his home, was a framed print of the final stanza of a poem by sportswriter Grantland Rice: “For when the One Great Scorer comes to write against your name, He writes not that you won or lost - but how you played the game." Clark’s life exhibited the spirit of the framed maxim. He was a man of great abilities and professional accomplishments. He also was modest and kind, and a man of faith.

Clark died on March 6, 2011, at age 85. At a memorial service, the Reverend Dr. Minka Sprague said that when a “great big life like Charles’s is complete, it feels as if a major star blinks out. The night sky, for this time, becomes darker still.”

Two retrospectives on Judge Clark’s career were published. “A Tribute to Chief Judge Charles Clark,” 12 Miss. C. L. Rev. 337-406 (1992). “Tribute in Memory of the Honorable Charles Clark,” 30 Miss. C. L. Rev. 389-460 (2012).